I know a lot of folks are probably thinking, "but how do I write a whole newspaper?" The good news is, you don't really have to. This process only requires writing four to six quick stories that follow the same rule I strive to follow as a GM: add the beginning of a story, but nothing more. The rest is for the party to decide. So let's brainstorm, and brainstorming is different depending on your purpose. The three commonest purposes for a newspaper are introducing a storyline, introducing a settlement, or chronicling something that the party has done. If you're introducing a storyline, you need your one main plotline, plus a few miscellaneous others; for a settlement, you want a mixture of new plotlines and characterizing details; and for a party deed, you need your one recognition story and a few miscellaneous others. In each case, most of what you need is a lot of ideas. So let's brainstorm!

I think I good breakdown for most newspapers includes the following:

1 leading story (either your storyline or a main quest)

2 secondary stories (best served by characterizing details and sidequests)

2 tertiary details (best served by characterizing details and sidequests)

1 humorous characterizing detail

This breakdown allows you to emphasize stories with different levels of stress--you have different tiers of importance to give to stories, allowing you to up-play or down-play whatever you want. Maybe you stress the story you're interested in, or you minimize it so your players feel like they found a hidden secret. It's whatever works best for you. With all this in mind, let's start working on an example.

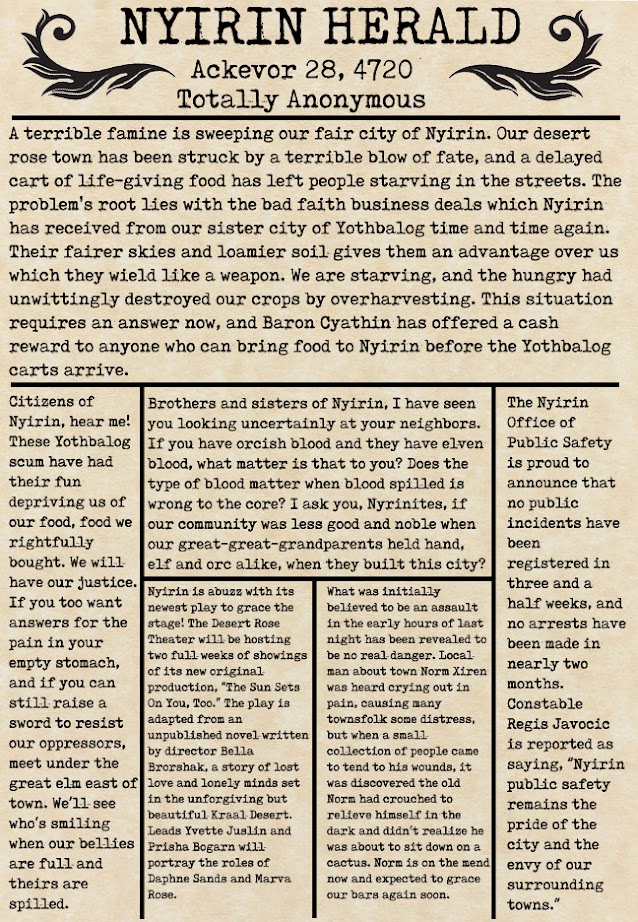

I'm not currently running a campaign that could use a newspaper right now, so I'll imagine that I'm making one for a settlement that some hypothetical adventurers have decided to visit. This newspaper will be basically their introduction to the town, and so I'm looking for quests and characterizing details. Let's say that this town is a desert outpost which recently missed a shipment from their food supplier. So their main story, and essentially a quest hook, is to gather food for the starving town. Another lesser story might demand justice from the town the missed the shipment, asking for a posse of adventurers to go exact revenge. Because the town is between orcish and elven country, there might be efforts in the newspaper to stir up dissent between those two communities, or perhaps a competing story asking for help smoothing things out. On the other hand, our characterizing details should tell us more about this town. Maybe it's uncharacteristically peaceful for being in basically a warzone, so there's a record of public arrests showing that no one has been arrested in weeks. Maybe it's a fairly cultured place, so one of the stories is about a community production of a play. And for the humorous characterizing detail, we might add that a locally well-known person had recovered from an embarrassing injury, which I'll say is sitting on a cactus while drunk. So we have some ideas.

To turn those ideas into full stories, we need to ask ourselves a few questions. What is this story supposed to be about? It should fill in details that make your other stories possible or which provide setting information. What is this place like? The story should reflect the place in some way so that it makes sense. What should the players take away from reading this? Remember that players will latch onto unimportant details with regularity, so focus your stories only on things that contribute to the direction you want to go in.

I'll turn one of these ideas into a story with some guidance along the way. Then we'll begin to prepare the visual representation of the newspaper. Let's work with the main storyline I brainstormed above about the food shortage. What is the story supposed to be about? It needs to explain the situation and propose a solution. So the article will describe the reasons for the food shortage and call for helpful people to donate and ship food, noting a blockage in the supply chain elsewhere. What is this place like? The city can grow a bit to sustain some of its needs, but it can't supply everyone. So with the growing hunger, people have destroyed the existing crops, worsening the problem. What should the players take away from this? That the situation is dire and that payment would be offered for help. So the article will specifically state the direness and name a benefactor who is offering payment. These answers resulted in the paragraph below, our story about the food shortage.

A terrible famine is sweeping our fair city of Nyirin. Our desert rose town has been struck by a terrible blow of fate, and a delayed cart of life-giving food has left people starving in the streets. The problem's root lies with the bad faith business deals which Nyirin has received from our sister city of Yothbalog time and time again. Their fairer skies and loamier soil gives them an advantage over us which they wield like a weapon. We are starving, and the hungry had unwittingly destroyed our crops by overharvesting. This situation requires an answer now, and Baron Cyathin has offered a cash reward to anyone who can bring food to Nyirin before the Yothbalog carts arrive.

I've written the other articles and will fill them in as we assemble the newspaper's appearance. Start by opening Photoshop and creating a new document with a 9 inch width and a 13 inch length. It should look like this:

|

| Our blank canvas. |

Then we're going to add an image of parchment texture. Once the image is in Photoshop, resize it until it covers the whole canvas. It should look something like this:

|

| Our blank parchment. |

Then add a title for your paper as well as the date (mine is in my gameworld's system rather than the Gregorian calendar) and some decoration:

Now it's time to add the text from the stories. It's not something that had a set way it has to be, but people generally expect different sections and columns. Have some fun deciding how big the text box are and how big you want the lettering to be. I'm going to emphasize my main story with bigger print and scale the rest down to fit. Remember to leave some space between the text boxes. I've also added a "Totally Anonymous" tag to the paper because (1) it's an interesting idea, and (2) I don't want to come up with author names.

|

| Text added. |

Now all we need are some formatting lines, and we have a newspaper. I suggest using the box highlighting tool to highlight where you want your line to be, then use the paint tool to fill it in using the same color of ink you used.

|

| Lines added. |

And then you have your finished product! If you meet physically with your players, you can print it out for them; otherwise, you can share it with them digitally as a part of your world.

|

| The finished newspaper. |

So, you can add lots of great characterizing information on your world, build for future quests, show the consequences of player character actions, and immerse your party into your world by taking some extra time to create something like a newspaper for your players. It took me about an hour and a half to create the newspaper and the documentation here to tell you how to do it, and you won't need to create instructions, so it's really just a matter of committing to be creative and making it happen. And think about how cool it would be to regularly make newspapers in-game and then have a record of all the plot points and storylines and player accomplishments. It's absolutely within your reach, so good luck.

That's all for now. Coming soon: why I use a combination of 3.5e and 5e, why most first-time D&D players are more Neutral than Chaotic-Neutral, and a list of interesting cities to use in your game. Until next time, happy gaming!