Alignment is, and always has been, something of a strange way to measure the values of a character. Quantifying morality and methodology is already challenging, and fitting each idea to only one spectrum? It's an odd thing to be sure. But I really like alignment. I think it helps us to understand our characters better, and thereby to roleplay more effectively. It's also especially helpful when a character changes--oftentimes, that comes during complicated times, and alignment can simplify that to reveal whether a character's beliefs are really changing. And along the way, we'll see that due to a misunderstanding about what alignment measures, first time D&D players, who often align themselves as Chaotic Neutral, are much more often True Neutral or Neutral Evil characters.

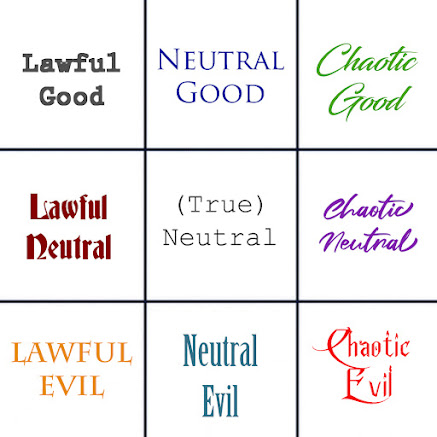

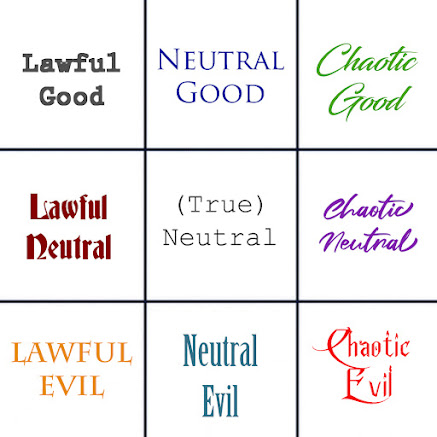

Let's start by addressing alignment. Here's an alignment chart, which is set up with morality up and down (good at the top, neutral in the middle, and evil at the bottom) and methodology along the sides (law on the left, neutrality in the middle, and chaos on the right):

|

| Fun with fonts. |

So let's talk alignment. Morality is relatively simple, but it's even simpler than most people think. Morality is defined in alignment like this: in a standard situation, do you choose to help people, hurt people, or not get involved? It really is that easy. I'll draw on a few of my characters to illustrate these ideas. Early in my gaming career, I played a gnomish wizard--he delighted in harming strangers and went out of his way to make things more painful for his perceived foes. This made him evil in the eyes of alignment, and complicating details wouldn't really change that. On the other hand, there was my very first character, an elven monk who was lawful neutral. He rarely got involved in others' affairs, and when he did take action, it was more often to fix problems or fight wrongdoers than it was to help people. So he was more neutral. Then we have my rogue/cleric I'm playing now. Over the course of the campaign, she's been more and more inclined to act based on helping people and healing the wounded. This is straightforwardly choosing to help people, so she's more of a good character.

Then there's methodology (law versus chaos). This is the one that's most often misunderstood. Law and chaos are not necessarily outright legal officers versus being random, even if that's the way it's construed by many players. Law and chaos are much more about the way your character thinks and solves problems. For me, the questions here are, "How much do you live by a routine? Do you tend to be organized? How much structure is in your life?" And perhaps most importantly, "Do you live by a code as opposed to judging situations independently?" If your character answers "yes" to these questions, then they live on order and are a lawful character. If they answered "no" to these questions, they are more struck by individual changes moment-to-moment and don't enjoy the structure of the world--they're chaotic. The in-between of this is being neutral--sometimes you do tried-and-true things, and other times you try new things. You're neither organized nor disorganized. Interestingly, I think this definition makes a compelling case that Robin Hood is not chaotic good as popularly argued; rather, because he operates the same strict way at all times (rob from the rich, give to the poor), he is actually lawful good. This is only the beginning of things we can learn when applying alignment.

Let's review methodology with examples. The gnomish wizard had a strict code: when it's possible to wreak destruction or hurt someone and get away with it, he would. Even when it seemed like a risky idea or was totally unnecessary, he would commit to what his code called for. He was a lawful character. The elven monk, on the other hand, was lawful for a totally different reason: he was a strict monk. His solution to everything in life was to turn to the teachings of his monastic upbringing, which teach him order, balance, and rigor. And so his approach to life was also lawful. My halfling rogue/cleric began as a character who was very balanced in terms of methodology--she sometimes relied on proven tactics, but just as often would take risks with new strategies that felt right at the time. She was true neutral in that regard. But she's been thrust into a crazy world full of surprises, danger, and colossal challenges, and it's all she can do to keep up by rolling with the punches, trying whatever seems like it might work. She's become chaotic as she's changed.

And speaking of that change, I'd like to draw attention to how alignment played a role in recognizing that change. The halfling rogue/cleric I'm talking about is Asp from

the novels I wrote about her as backstory for my playing her. Because I've written so much about her and spent so much time in my head with her, I've been very much too close to the matter to see it clearly. I spent each session trying to gradually show her change from true neutral con artist to chaotic good healer, and to do so in a way that was natural and compelling. It was hard work, and I could never tell if what I was doing was working. But we levelled up after our last session, and I found myself staring at the alignment setting on my character sheet. I kept thinking, "Is my character really true neutral still?" I kept thinking about the ways she behaved in-game recently--stopping conning people to get ahead, healing several people, being more honest--and I couldn't tell if she had changed

enough to merit an alignment change. And then I asked myself the above questions about her. "Does she hurt or help people?" She helps as often as possible. "How structured and ordered is her life?" She has no routines and is trying to create a new life. She makes decisions by intuition. No longer was Asp a smooth talker with no claim to values of any type--now she was a new person, and the alignment chart helped me to recognize that and keep the creative process going.

So, how is it that first-time players, who so often cast themselves as chaotic neutral adventurers, are really true neutral or neutral evil? One more time, let's go back to the alignment questions. These players cast themselves as morally neutral. Does this hold up to scrutiny? Do they actively help or hurt people? I accept neutral as an argument for some of these adventurers--they hurt and help indiscriminately, and the balance makes them more or less neutral. Some do tip, though. Many of us have played with gamers semi-affectionately referred to as "murder-hobos," characters who simply cut a path through the imagined space killing and looting as they see fit. Do they hurt or help? Well, the balance tends to lean more towards hurt than help, and the little help being done is usually for the sake of reward, negating most of the moral reward. If we were using the expanded 5x5 alignment chart that offers half-steps between each choice for more accurate coordinates, I would say that most beginning players end up in the place between true neutral and neutral evil (which uses the term "neutral impure," which I don't like, so just think of a half-step).

More importantly, though, most beginning players are not chaotic. This is due in part to a misunderstanding of what chaotic means. There are law officers who are chaotic and criminals who are lawful--it's not a measure of obedience of the law. There are eccentric people who are lawful and plain people who are chaotic--it's not a matter of personal expression or "randomness." And there are people who live average lives who are chaotic and people with strange lives who are lawful--it's not a measure of anything but what the character is inclined to. All that matters is how much structure is in the general lived experience of the character.

So are beginning players chaotic? In a sense, I suppose. They're trying to figure out the game, so they experiment with it, trying new things. At the same time, just as often, players figure out how to attack and roll a few skill checks and stop experimenting--by that measure, beginners are generally neutral as far as law and chaos goes. Very few beginning players live by a code of any type, but neither do they vary their actions unless required; rarely are beginning players fluent enough with the game to be very organized, but their disorganization is not disorganization of the character as the player's own struggles; there's little structure in the life of an adventurer who runs from encounter to encounter, but this is again a meta-choice by the player and not necessarily indicative of a character trait. That's not exactly the portrait of chaos that many players strive for.

Why should this distinction matter? Alignment can be helpful, as I noted with my changing alignment issue above. It can be a fun point of discussion--I remember on multiple occasions debating whether a character in a party I ran was chaotic neutral or chaotic evil (I was arguing for evil), and those conversations wouldn't have allowed for philosophical debates if not for alignment. And alignment also helps to be familiar with so that the various in-game rules about damage effects based on alignment make sense when they come up. It may be obtuse and bizarre to describe mentality this way, but it can be a fun addition to your experience of the game. (And if you're thinking that alignment sounds kind of off and wouldn't be fun or helpful, you could try

these alternate methods to characterize your character's philosophy and values.)